Conversations on Art: Lia Halloran

Lia Halloran. Bronson Canyon, 2014/2019, Passage | Dark Skate, edition 1 of 3, c-print, 32 x 84 in. Image courtesy the artist and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

Lia Halloran traverses through mechanisms of experimentation in order to document motion of matter. As an interdisciplinary artist, Halloran examines the interconnectivity of scientistic cultures and the performance of light. Halloran recently presented Your Body is a Space That Sees at LAX Terminal 1, as well as a solo exhibition, The Sun Burns My Eyes Like Moons at Luis De Jesus Gallery in Los Angeles. In this interview the artist deep dives into the creation of cyanotypes, her Dark Skate series, and the influences of mythology and science on her practice.

Halloran is represented by Luis De Jesus Los Angeles, and is an Associate Professor of Art at Chapman University in Orange, California, where she also teaches courses that explore the intersection of art and science. Halloran is currently an artist-in-residence at the Division of the Humanities and Social Sciences as part of the Caltech-Huntington Program in Visual Culture. @liahalloranstudio

RICKY AMADOUR: Within the greater body of your successive projects there is an interdisciplinary subjectivity. Let’s start with the Dark Skate series - what prompted your investigation?

LIA HALLORAN: Well first of all, I would totally agree with you on the interdisciplinarity within my work. There’s moments where I look around my studio and it almost looks like there could be multiple people working in here, and there is an opportunity to discover a new way to work. I had never made a cyanotype before I had made the series Your Body is a Space that Sees. I had never made a photograph before I made the Dark Skate series - essentially I had a concept that would form and would try different mediums until I found the right one that would fit.

AMADOUR: I would’ve never known that you were experimenting as they are meticulously created.

HALLORAN: It’s years in the making. It took 6 months before my first successful cyanotype print. They are made by painting on a translucent piece of drafting film. Not only is my work about science or drawing from science, but the process itself always has an experimental quality. It's an opportunity to learn something new but it does take a long time. I made a video called Double Horizon about time splitting and figured that a video would work best as a time-based medium. It took two and a half years to figure out how to make one eight-minute video, and built into it all is a kind of fundamental pleasure in the failure of discovery.

Lia Halloran. Bike Path, 2018/2019, Passage | Dark Skate, edition 1 of 3, c-print, 48 x 48 in. Image courtesy the artist and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

AMADOUR: Going back to the Dark Skate series - are these developed by recording yourself while skateboarding and a long exposure?

HALLORAN: I’m from the Bay Area and my dad is an incredible surfer. I got my first skateboard when I was four years old and grew up surfing and skateboarding. In essence, I was interested in capturing the physics and movement of skateboarding in a way that explores Los Angeles’ urban landscape and memorializes the 6th Street Viaduct - which is being rebuilt.

AMADOUR: By Michael Maltzan?

HALLORAN: I've seen the new bridge in construction and I think it's going to be a walk bridge, but yeah, this one is gone. The Dark Skate series is basically a performance. It captures my childhood as a female skateboarder and as a kind of lone person. In the nineties in San Francisco, skateboarding culture was on one of its biggest booms. I was in Thrasher magazine when I was 15 years old and around all these skater guys - but there weren’t any women or girls. It was so male-dominated that I always was like the other, you know - it’s almost like a double layer of queerness. Like the ‘othered’ other - which is inherently sort of built into my work by always highlighting stories of otherness or the invisible.

AMADOUR: Literally, although you are skateboarding in your photographs, you have an invisible body. The viewer is only exposed to the documentation of light in the image - there isn’t a sex or gender - just a visible stream of light.

HALLORAN: It's really like a haunting or graffiti. I'm always the performer and I work with photographer Adam Ottke - who’s fantastic - he and I have been doing this for almost ten years together. And before that, I worked with another photographer, William Mackenzie-Smith. We’re using Hasselblad cameras or other medium format cameras - in this case, a panoramic camera, all done with film. And then, like you noticed, the shutters left open for upwards of forty-five minutes to an hour. I've done this series now in several different cities including Vienna, Miami, and Detroit - starting with places that I used to skateboard.

I used to have an all-girl skate crew called RIB DEATH and these were places that we would actually just skateboard. There are all these places in Los Angeles that are meant for water and because we're in a desert, there is no water there. I’ve always been amazed by the way in which cities are surrounded by water. You think about the most famous cities in the world, San Francisco, Paris, Rome - everything is near water, right? But here in Los Angeles we pass waterways going seventy miles an hour on the freeway - and most people have never been in the rivers. And so I question how we can recontextualize or learn something new about our environment through the action of motion. As explorations of urban space these works are self-portraits. This is the way I would explore it, if you did it, you would explore it in a completely different way. They are also portraits of Los Angeles.

AMADOUR: So you showed these photographs alongside the video of Double Horizon. Would you describe the creation of the video?

HALLORAN: I was learning how to fly an airplane over a period of two years and I attached cameras to the exterior. In Dark Skate, I attached a light to my wrist and tried my best not to draw or get a specific line.

AMADOUR: You’re a pilot as well?!

HALLORAN: Yes I am! [moments of laughter]

AMADOUR: You’re incredible.

HALLORAN: I thought this was such an eloquent curatorial decision - but I was in a show at the Guggenheim Museum called Haunted: Contemporary Photography/Video/Performance and the curators placed my work in the section of performance. Although the camera is the necessary interjection to record the performance, the work is about how I'm moving through the space. For Double Horizon, I attached the cameras to the exterior of the plane right before I called the tower to do my final takeoff call and pushed record as I flew around. And so the Double Horizon is very similar in that way - it’s about how something you see all the time can become fresh and new to you.

Maybe it's through a change of perspective, a different time period, or the action of motion? For Double Horizon, it was really important that I pilot the plane and most of the time I'm alone in the plane. There's one place that I wasn't allowed to go to by myself and that's Catalina island - my flight instructor was in the cockpit. Every time I see this image, especially in the video, there's a crescendo of sound - Allyson Newman composed the original score. You feel the vastness of Los Angeles looking at this piece.

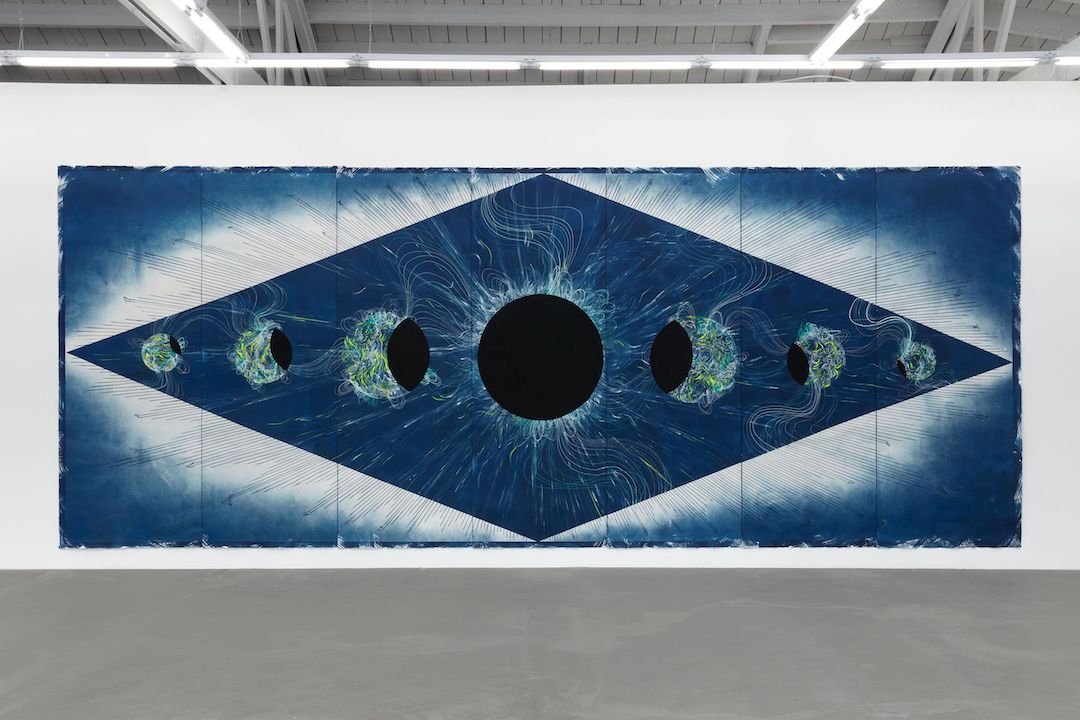

Lia Halloran. The Sun Burns My Eyes Like Moons (Positive), 2021, cyanotype on paper from painted negative, acrylic, and ink, 119 x 300 in. Image © Lia Halloran and courtesy Luis De Jesus Los Angeles. Photo by Paul Salveson.

AMADOUR: Going back to your cyanotypes, could the process in which you use to create them be a performance as well? Your cyanotypes explore notions that question what is ‘science’, what is ‘religion’? Which could go deeper into the cyanotype process being a type of elemental performance in which the sun is performing. Is the protagonist always human?

HALLORAN: I've always talked about my cyanotypes as being so predetermined by what is going on in the sky. They’re seasonal and are made between May and October. All of our curiosity is like a speed limit set by technology. My next piece in the works is a machine that's going to set its own parameters and creates the work - or is the machine the work itself?

AMADOUR: Performance is truly all encompassing.

HALLORAN: I have a residency at Caltech currently. It's a joint research position at the Huntington. So I get to access all the archives at the Huntington and I'll teach a class at Caltech. But my project that I applied for the residency with was about how machines between Mount Wilson Observatory and LIGO, the gravitational wave detector, and how those machines give us the parameters of what we even understand. So let's dive into those machines and then I'll make a machine about those things. Essentially, making a machine to create a work about those machines in the same way that I used the sun to make a series of work about stars and the sun.

AMADOUR: Artists in my periphery have been interrogating the social sphere and the constructs of spaces like social media. We are using devices both digital and physical on a daily basis, but have no comprehension of how they function or their total capabilities. We just take it for what it is and for granted.

HALLORAN: Yeah, absolutely. I know. It’s like Brave New World, The Matrix, Terminator - things made into some sort of strange dystopia. We're just so excited by the progress of technology that we don't question the implementations, effectivity, or future sustainability of that technology.

AMADOUR: And what is the sustainability of the technology we consider renewable?

HALLORAN: Everyone was pushing for solar for so long and then it seems like six months ago, this conversation that you're talking about has become relevant.

AMADOUR: Going back to the cyanotypes that focus on the sun I want to ask - can you be spiritually and scientific minded?

HALLORAN: Well this one was inspired by seeing a total eclipse for the first time in my life in 2017. I had read a ton about eclipses and how amazing and transformational they are. And when I was witnessing it in Oregon, it was the most shocking thing I had seen in my life. In that moment it doesn't matter that the moon shadow is doing X and the earth is located here and the sun is located there. You're just having a transformational experience.

AMADOUR: In a way it's a bit rebellious. I think that your work really transcends those binaries and forces an interrogation.

HALLORAN: Paul McCarthy was one of my professors when I was an undergrad at UCLA. One of my favorite things he ever told me was that after he makes something, sometimes it takes upwards of six months to know what he did. That gave me permission to not always know the direction that I'm going in. And so earlier I had mentioned being uncomfortable with failure and discovery - I actually put those two together. That is so embodied by what Paul was saying, like you have an action, you're an artist, you have an impulse. Every mark I make is built up from the lineage of marks and years before of all those other marks, it’s in my arm somehow.

AMADOUR: Could you tell me about the hands in The Sun Burns My Eyes Like Moons?

HALLORAN: The research for this piece includes multiple directions and inspirations. One is contemporary solar observatories. The other one is from solar astronomer George Ellery Hale who founded Mount Wilson Observatory and was the inventor of the solar telescope. When you’re driving through Pasadena and see the very tall hundred foot dome that looks like it's on stilts - it’s a solar telescope where he did most of his research. Later in life, he started to kind of go crazy and wanted to build a solar telescope in his backyard in San Marino. Solar telescopes have to be really tall - and they figured out a way to build a telescope in his backyard by digging two stories down. So the telescope, you kind of enter on the ground level and then you go down to the basement.

AMADOUR: Does it still exist?

HALLORAN: Yes, it's in someone's backyard which was George Ellery Hale’s old house. The front of the facade of the solar telescope is very elaborate and has this image of the sun and these hands emanating like rays. When I first saw it, I was like, whoa, this is so strange - it’s clearly some some sort of Egyptian reference. It turns out that Hale was sick later on in his life and felt that traveling to Egypt where his friend had discovered King Tut's tomb could heal him mentally or physically in some sort of way.

And so he borrowed the icons and the sun icons of the gods from the facade of King Tut's tomb and had them carved into his backyard solar observatory. The images in The Sun Burns My Eyes Like Moons, 2021, are double fold as a reference to Hale. They are also reaching back in time to the Egyptian gods. The rays in general also reference early Renaissance depictions of godliness.

How would you know that someone was chosen? Because they would have light emanating from their heads. Now we commonly see a halo, a crown, an orb of light, and know what that means. But if you think about it more clearly, this incredible divinity is actually the representation of light.