Review: Experiments on Stone - Four Women Artists From the Tamarind Lithography Workshop at Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego

Anni Albers. Line Involvement I from the Line Involvements Suite, 1964. Color lithograph. 19 3/4 x 14 1/2 in. (50.2 x 36.8 cm). Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Martin L. Gleich, San Diego, 1970.34. © 2021 Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“An artist is an artist, and the medium is only a vehicle,” wrote June Wayne in a 1969 letter to Anni Albers following the artist’s residency at Wayne’s storied Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles. Wayne, an established printmaker and painter, had written to Albers that for the first time in her life she was planning to try her hand at tapestry design.

For Wayne, play and experimentation were integral to the process of creating art. Creativity was not tied to any one particular medium, but instead enhanced by working across multiple, trying something new and collaborating with other artists.

This was the type of environment that Wayne sought to create when she founded her Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Hollywood, California in 1960—one of play, collaboration and innovation. At Tamarind, artists could experiment in what for many would be a new medium of lithography and collaborate with the workshop’s master printers who were skillfully trained in the art. With Wayne at the helm, the Tamarind Lithography Workshop was itself a grand experiment, bringing in different artists every two months and resulting in nothing less than a print revolution in Los Angeles.

The artist Gego with master printers of the Tamarind, 1966. Photographer unknown. Fundacion Gego Archives. © Fundación Gego

Remarkably, Wayne’s workshop singlehandedly resuscitated the art of lithography in the United States which had become a dying medium due to increasing economic pressure and a scarcity of skilled master printers just after the midcentury. Between the years of 1960 to 1970, Wayne transformed the quality and status of printmaking, bringing nearly 150 artists into residence including Josef and Anni Albers, Ruth Asawa, David Hockney, Sam Francis, Francois Gilot, Philip Guston, Louise Nevelson, and Ed Ruscha, among others. Wayne’s work at Tamarind was crucial in not only furthering the development of the medium, but also the careers of countless artists—many of whom were women.

Four of these women artists and the prints they created during their time at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop during the 1960s are the subject of an online exhibition currently on view on the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego’s digital platform, MCASD Digital. Experiments On Stone: Four Women Artists From The Tamarind Lithography Workshop, curated by the museum’s former assistant curator Alana Hernandez, brings together the prints of Anni Albers, Ruth Asawa, Gego, and Louise Nevelson, all of whom completed two month fellowships there. The four artists, all known for working primarily in mediums outside of printmaking—Albers in weaving, and the others, Asawa, Gego, and Nevelson in sculpture—utilized their time at the workshop to continue their exploration of space, however, this time, on a two-dimensional plane.

The online exhibition, with a page dedicated to each of the four artists, showcases the lithographs they created during their time at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop alongside some of their more famous, three-dimensional works. Demonstrating the continuity between each of the artists’ works, the exhibition reveals how certain ideas the artists were exploring transcended mediums and were perhaps even enhanced by their expression in lithography.

Gego at Tamarind Lithography Workshop. Los Angeles, 1966. Photographer unknown. Fundacion Gego Archives. © Fundación Gego

Gego. Untitled (TAM. 1845), 1966. Color lithograph. 22 1/4 x 22 1/8 in. (56.5 x 56.2 cm). Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Martin L. Gleich, San Diego, 1970.163. © Fundación Gego

Gego and Albers, for example, were fascinated with the line, and Nevelson, with transforming found materials. Gego (born Gertrude Goldschmidt) was an artist known for her kinetic sculptures and installations in the 1960s and 70s in Venezuela. She was the only artist of the four who worked consistently in printmaking before coming to Tamarind, however it was during her two residencies there that she experimented with new concepts, namely the line and its instability, which would have an impact on her later sculptural works.

Anni Albers. Enmeshed I, 1963. Color lithograph. 20 1/4 x 27 in. (51.4 x 68.6 cm). Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Martin L. Gleich, San Diego, 1964.109. © 2021 Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

What Anni Albers, a prominent Bauhaus weaver, discovered during her time at Tamarind was a certain freedom of expression offered by the lithographic medium which she felt lacking on the loom. Working on paper enabled her to set the line free—creating images depicting a single line exploring space, or loosely woven threads appearing at the risk of unraveling yet suspended on the picture plane for eternity. Albers came to Tamarind with never before having worked in lithography, and by the late 1960s, she turned exclusively to printmaking and never looked back.

During her residency in 1963, Louise Nevelson, a sculptor who frequently used found materials to build her blocky, monochromatic sculptures, similarly completed twenty seven prints in the same familiar hues by pressing found objects such as lace and erasers onto the lithography stone.

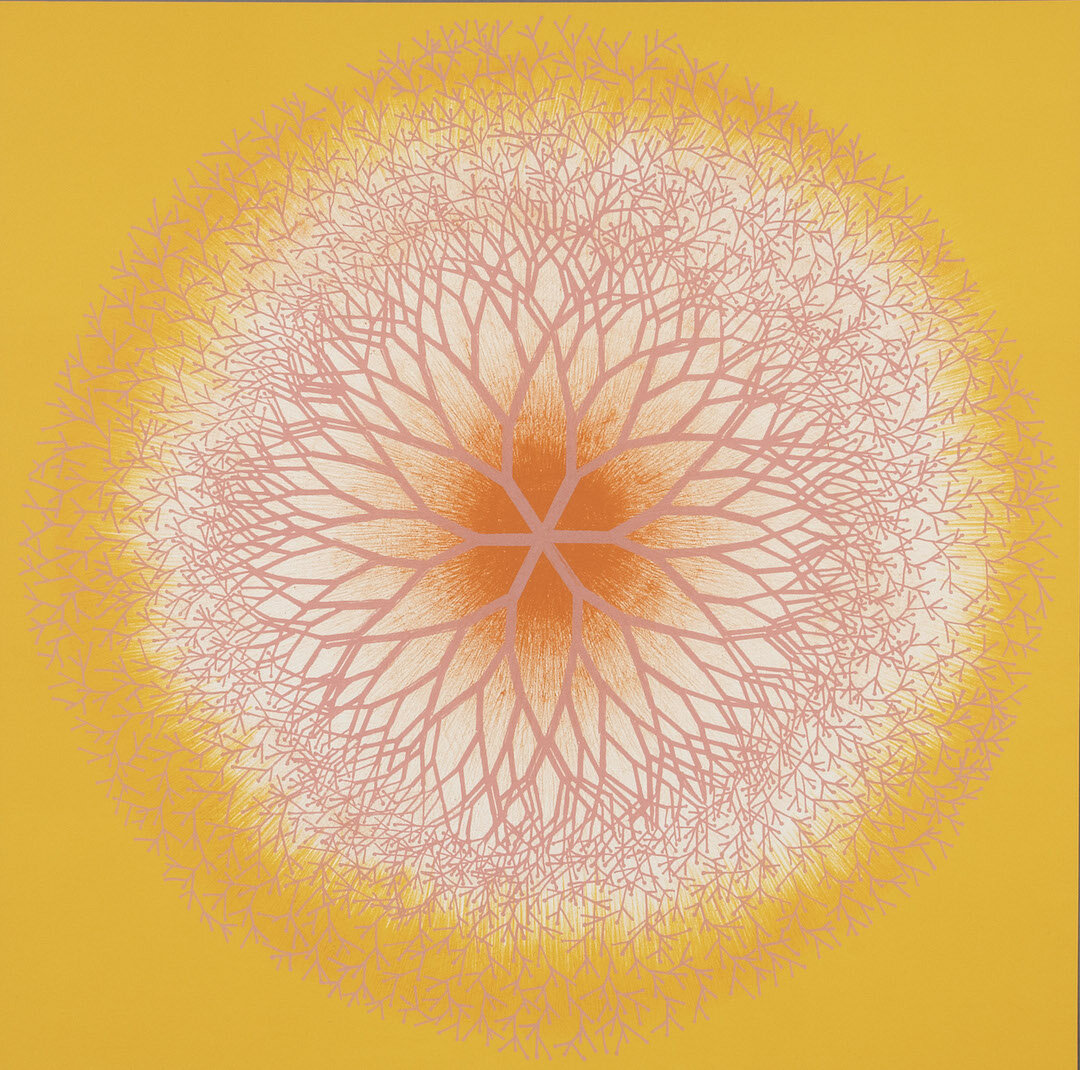

Ruth Asawa. Desert Plant (TAM.1460), 1965. Color lithograph. 18 1/2 × 18 1/2 in. (47 × 47 cm). Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Martin L. Gleich, San Diego, 1970.111. © 2021 Estate of Ruth Asawa / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Of the four artists exhibited, however, Ruth Asawa’s time at the Tamarind Workshop was unmatched with regard to sheer artistic output and variety of subject matter. As the second Tamarind fellow never arrived at the studio during Asawa’s fellowship, the artist benefited from having the attention of all seven printers at the workshop. Described by Wayne as “a love affair between Tamarind and Asawa,” her fellowship resulted in the manifestation of an incredible fifty-four prints despite her never working in printmaking before.

The bulk of Asawa’s works from the Tamarind are investigations of the natural world. Not unlike her undulating sculptures, she created organic forms of trees, flowers, and desert plants that blended into obscurity and abstraction. She also created lesser-known, figurative works which featured portraits of family members.

The Tamarind Lithography Workshop existed under Wayne’s direction until 1970 when it was transferred to the University of New Mexico at Albuquerque under the new name of Tamarind Institute. Leaving the workshop enabled Wayne to refocus her energies on her own art. As living proof of her own statement that “an artist is an artist and the medium is only a vehicle,” Wayne went to Paris to explore the possibilities of tapestry design. There, she used several of her lithographs as the basis of twelve tapestries created between 1970 and 1974 in collaboration with master weavers of France.

The exhibition, Experiments On Stone: Four Women Artists From The Tamarind Lithography Workshop, can be accessed online through the summer.